Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (PlayStation) Review

By Gabriel Jones  27.03.2017

27.03.2017

It is said that Dracula resurrects every hundred years. When that time comes, a Belmont wielding the Vampire Killer would make the perilous journey to slay the Dark Lord. In the year 1797, five years after being destroyed by Richter Belmont, Dracula rose once again. With this event, the hundred-year cycle had been broken, creating an age of darkness that none will survive. Now, it is up to Alucard, son of the infamous Count, to enter the dread castle and restore the cycle.

Upon its release twenty years ago, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night received unanimous praise from everyone who ever picked up a controller. Even today, it's heralded as a classic and considered to be one of if not the best entry in the franchise. This game has astonishing visuals that are backed by an absolutely gorgeous soundtrack. The controls and mechanics are superb, owing to Konami's experience in crafting masterful action-platformers. Dracula's Castle, from basement to attic, is loaded with secrets. However, the purpose of this review isn't merely to preach to the choir.

If a concept serves as the heart of a game, then ideas are what give it veins and arteries. Not all ideas are perfect or even good, but their existence is required in order to make great games. This entry in the franchise stands out, simply because it has the most ideas. If anything, future titles such as Aria of Sorrow and Order of Ecclesia attempted to rein in some of that boundless inspiration. They made more of an effort to focus on the strengths of the Metroidvania series, and might be considered better entries for doing so. It's fair to say that limitations are a necessity, because they help to keep the game grounded.

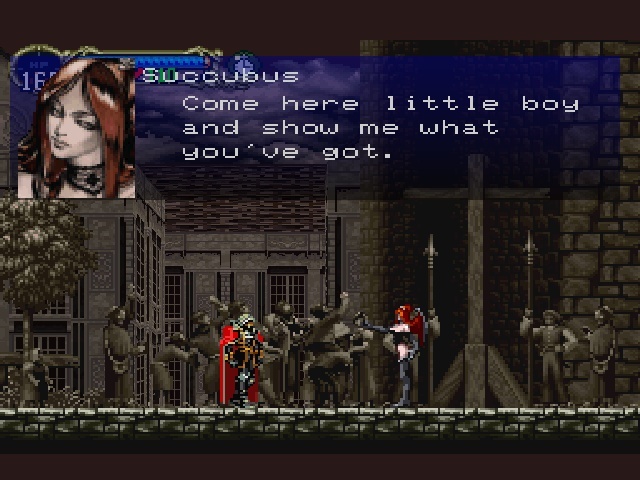

To better explain the problem with too many ideas, let's start with the protagonist. Alucard is quite possibly the most overpowered hero in videogames. Barehanded, he's more than adept at handling the inhabitants of his father's castle. Eventually, he can turn into a bat and fly anywhere, or dissolve into mist to dodge any attack. His knowledge of the dark arts includes a spell that drains the life of everything in the immediate area. While Death had the bright idea to steal Alucard's equipment early on, he probably should have done something about all of the great stuff just lying around.

In the right hands, the half-vampire is already a force to be reckoned with, but he becomes entirely unstoppable in a short period of time. The Crissaegrim, absurd as it is, is just one path to becoming a destructive force of nature. The Shield Rod, when paired with Alucard's shield, can also snap the game in half. A pair of chakrams can chew through practically anything in seconds. Don't like getting close? Just beat up on a defenceless bird until it drops one or two flying Runeswords. Even if Alucard avoids all of this great stuff, he's liable to become ridiculously strong, just from all of the levelling up he does.

There are plenty of other ways in which the protagonist can tear everything to pieces. Items such as healing potions are commonplace. Familiars, with enough experience grinding, can destroy foes as soon as they appear on-screen. Alucard can also wield daggers and holy water as well as any vampire hunter. It's possible to discover armour and accessory combinations that trivialise almost any encounter. Even the "super boss" Galamoth is no match for the almighty beryl circlet.

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night doesn't know the meaning of the word "restraint." Thus, the player will have to find it within themselves to achieve a somewhat balanced difficulty. To put it another way: the players are what make this game a classic. All of the tools and techniques that are discovered in the Castle can be utilised in a manner that makes every playthrough interesting. This isn't limited to attempting to beat Dracula without weapons, spells, and armour either. What if Alucard couldn't throw a single punch, and had to rely on familiars? Maybe he could try to go as far as possible using just the special weapons, such as daggers or throwing axes. These limitations probably aren't entirely feasible, but they're worth attempting. Essentially, Dracula's Castle becomes a giant "toybox" filled with fun things to play with, whether they're weapons or enemies.

On its own, the level design isn't particularly great. While the castle is sufficiently large, most of its hallways and rooms are rather vacant. Sure, there are plenty of obstacles in the form of monsters, but this highlights a problematic aspect lying at the core of Konami's "Metroidvania" efforts. In Metroid, enemies served a supplemental role. Most of the challenge was in navigating each room, finding the path forward, and obtaining all of the items. Since the architecture of the average room in this game isn't nearly as complex, the enemies take on the primary role. This does little good, since it's already well established that Alucard can cut through everything as if it was never there.

As with its quasi-inspiration, getting through the Dracula's Castle as swiftly as possible requires a high level of execution. This is another way in which the surplus of ideas can benefit the game. Thanks to techniques such as the back dash and the wing smash, the hero can move through the castle very swiftly. However, wing smashing requires a fairly tricky motion, and travel can be cut short by a missed input or a crash. Eventually, this method of traversal becomes second nature to the player, simply because they're performing the move so frequently. These unique abilities help to make level design more intriguing, simply because the player is more involved in the process. This is much better than just having Alucard jog forward while slashing.

There's also something to be said about "comfort gaming." Call it nostalgia, but there's a certain idyllic feeling in trekking through Transylvania's most popular nightspot. It helps that there's so much detail in every scene. Even the most frequent visitors will be impressed by something they had never noticed before. For example, there's an amusing detail in the fight with zombie Trevor, Grant, and Sypha. If Sypha is the last to survive, she'll continually summon Trevor's mangled corpse to shamble at the hero. It's a pretty ineffective attack, but charming nonetheless. Basically, this is one of those games that could be replayed at least once a year and still be entertaining, even without player-imposed conditions such as "no weapons" or "fire attacks only."

Cubed3 Rating

Exceptional - Gold Award

The true test of a game's quality is determined by how well it has aged. More often than not, the first playthrough will be looked upon favourably, simply because the player doesn't know what to expect. Castlevania: Symphony of the Night makes for an incredible first impression, that much is certain. Over time, however, its weaknesses have become apparent. Alucard's solo adventure suffers from mediocre level design and uneven boss fights. Still, in terms of ambition, it remains unsurpassed. Though tarnished, this gem retains its brilliance because it offers so much freedom to anyone who plays it.

![]() 9/10

9/10

![]() 0

(0 Votes)

0

(0 Votes)

Out now

Out now  Out now

Out now  Out now

Out now  Out now

Out now Comments

Comments are currently disabled

Sign In

Sign In Game Details

Game Details Subscribe to this topic

Subscribe to this topic Features

Features

Top

Top